Lighter than air

28 July 2016Airships are set to return to our skies with projects planned across the world. Rhian Owen investigates why there is a new-found attraction of airships such as the Airlander in the UK, and how remote construction projects could benefit.

On May 6 1937, thousands of people looked to the sky to watch the Hindenburg land in Lakehurst, New Jersey, according to archival newscasts of the German airship.

On its final trip across the Atlantic, footage of the landing shows people cheering, and then screaming as the aircraft ignites into flames and crashes to the ground. Within a minute, the airship was destroyed. 97 people were abroad and 36 people died in the accident.

Prior to the Hindenburg, airships looked like the future of commercial air travel. Airships were the ¬ rst aircraft capable of controlled powered flight, and were commonly used before the 40s.

“In the 19th Century it was realised that instead of using hot air a lifting gas like hydrogen could be used, and if you put some early motors on to the airships, rather than having a balloon that acts depending on the wind, you could have an aircraft that can move in the direction you want,” says Andy Barton, business development director, Hybrid Air Vehicles (HAV), says.

The airship industry has marked some momentous achievements. “The first airline passenger service was an airship service; the ¬ rst aircraft to make a transatlantic flight both ways in 1919 was an airship; the ¬ rst aircraft to y across the North Pole was an airship; and the first one to y around the world was an aircraft,” says Barry Prentice, president of ISO Polar Airships, a non-profit organisation devoted to the promotion of the airship industry.

“Before 1940 there were a lot of achievements. There are questions around why airships aren’t so prolific today, and fingers point to the Hindenburg accident. But that is not the case. So the question is, why did the airships disappear? The answer is they decreased over time as the jet engine and jet passenger aeroplanes were adopted.”

The Comet was the world’s first passenger jet airliner. Designed and built in Britain, the Comet took its first flight in 1949. It revolutionised air travel, and was the pride of the British aviation industry, until 26 October 1952 when the Comet crashed and all five crew and six passengers on board were killed. The accident was the first fatal jetliner crash. By the time the Comet was redesigned and re-certified for commercial service, the American aircraft manufacturer, Boeing, released its 707 passenger jet, which could carry almost twice as many passengers as the Comet. The new American airliner cornered the market.

“The jet aeroplanes took the airship from the sky, the ocean liners out of the seas, and the passenger trains - in North America at least - were no longer prevalent either. The jet aeroplanes were such a dominant technology that the only thing left for the airships to do was to be floating billboards. So that was the only practical use for the blimp and its cousins for the last 70 years. As a result of that the world has this notion that’s all they can do,” Prentice says.

Attempts to bring airships back to commercial operation have floundered in the past, but the golden years were never forgotten. Now, many aviation experts believe the reemergence of the airship has arrived, with renewed interest in airships across Europe and North America, albeit for a different market. Today’s airships could be used to transport heavy industrial equipment direct to the customer.

Airships can lift equipment to remote locations as they do not require runways or miles of roadway necessary for conventional air and truck transport.

The industry’s future is initially aimed at transporting goods where roads and airports don’t exists - Canada’s frozen north, China’s western frontier, remote parts of Africa and Islands in Asia and South America.

In Canada, airships have the potential to compete with trucks, where new, costly ice roads must be constructed in order to transport goods to northern communities. In addition, warming winters are making seasonally-constructed ice roads less reliable.

“Canada has a very low population so it’s hard to justify building bridges and roads to areas to areas to serve 600 people,” says Prentice. “We have remote communities that are scattered throughout our north that are either served by little aeroplanes or by ice roads. Historically, the ice roads were open three months during the winter but now it is lucky if they are open for four weeks. The airships can replace the ice roads and that’s a major benefit.

“In the north, as soon as you get beyond the roads all the prices double or tripple including food. It’s very expensive to live there and to do any developments. However, Canada’s most attractive mineral resource developments are located in the far north.

The airship industry could revolutionise the development of northern Canada and make it a much more inviting place to undertake economic activity, and to live. It could have a huge impact on Canada, and other countries with similar issues.”

What’s more, airships cost less money and emit less pollution than aeroplanes. Not all cargo needs to travel at 800km per hour, and the aviation industry is a major source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

“There is a global need to replace some of the polluting aeroplanes that are carrying cargo around the world,” says Prentice. “When an aeroplane gets old and replaced for passenger use with something newer, that old aeroplane doesn’t go to the breaker’s yard, instead it gets altered, things come out and a new door goes on, and it’s a cargo aeroplane. So all the jet cargo aircrafts are the most polluting aircrafts we have. And we could replace all of those with airships. I think that’s a really important need.”

These days it is inert helium gas that is used to float airships in the skies, rather than highly flammable hydrogen. Barton explains: “Hydrogen does provide more lift than helium, but it is highly flammable whereas helium is inert and can act as a fire extinguisher. The reason why we use helium is that it is safe and the aerospace regulations forbid us from using hydrogen as a lifting gas.”

However, Prentice says that this is providing a barrier to the airship space returning. “All of the airship projects around the world are designed to operate on helium. Helium is expensive, it’s mined but not produced, and has other uses that compete for it so its price is high. The alternative gas, which is hydrogen, is unavailable to the airship industry because it has an absolute ban. The ban has not been based on science or engineering - there has never been a case that an airship caught fire because of the use of hydrogen. So here at the University of Manitoba we are pushing that.

What do you mean we can’t use hydrogen safely? What’s the justification for this? What’s the science behind it? Plus, today we have airworthiness regulations; it takes years for an aircraft to be certified so there is no need to have a ban on hydrogen when you already have this process to prove it’s safe. I think it’s holding back the industry.”

Nonetheless, there are dozens of projects out there. In the UK, the 302ft (92m) long Airlander 10 - part plane, part airship - is getting ready for takeoff. HAV assembled the airship at Cardington Sheds in Bedfordshire, a site that has been associated with airships since 1915 when Shorts built the first giant hangar to build the R31 and R32.

The Airlander 10 prototype, which HAV hopes will be the first of 1,000 craft, is 25 per cent larger than a Boeing 747 and is designed to remain airborne for up to five days.

“Now it’s a civil aircraft it has to have a pilot. We can carry 10t and because we have pilots on board we are limited to being airborne for five days, as opposed to three weeks,” says Barton. “If in the future civil aircrafts can fly without pilots we will go to three weeks again.”

Unlike traditional airships, the Airlander 10 is not susceptible to high winds - the aircraft is able to take off and land in winds of up to 35 knots - and it doesn’t need a large ground crew for take-offs and landings.

Barton also explains that the Airlander 10 is capable of vertical take-off and landing and that customers “need just four times the length of the aircraft to land, so that’s 400m”.

Barton adds: “Provided you have that kind of clearing, we don’t need a runway to land. So if the build site has that space then we can land in a remote area and deliver the logistics directly.”

Prentice adds: “It is easy to exaggerate what can be done. What we do know is that the old Zeppelins would carry up to 70t of useful load, and certainly what we did 80 years ago can be done today. So we know we can lift 70t but there hasn’t been an airship built in the last 80 years that can lift more than 10t. The one that you have being built in England today will lift 10t, and that’s the biggest airship in some 60 years. But this is just the beginning. We know we can make aiships that can carry more, and with today’s technology and engineering there are a lot of experts that think that 250t is quite achievable.”

Barton agrees and says that the Airlander 10 will be used mostly for search and rescue, reconnaissance, communication and aid distribution purposeses. In order to deliver very large, heavy equipment and transport them in one piece from a fabrication plant to a site, then lower into the exact location, or use them in an area where trucks and cranes cause congestions or cannot be fitted, Barton says a larger aircraft will most likely need to be used.

Around 60 percent of the Airlander 10’s lift is created by the buoyancy of lighter-than-air helium gas, while a further 40 percent lift is generated aerodynamically by having a wing-shaped hull. The engines can be rotated to provide an additional 25 percent of thrust up or down, to help landing, take-off and hover.

“But that extra 40 percent aerodynamic lift is providing you’ve got an air speed of 20mph, which means we would have to come up with an operational plan (in order to make direct installations). So if we’re looking at installing wind turbine blades from an airborne hover without the 40 percent of aerodynamic lift, maybe it will work but my hunch is a bigger aircraft will be needed, such as what we’re working on next; the Airlander 50.”

HAV is exploring a future model with a 50t load capacity and is intended primarily for heavy lift and cargo transport. It also features an air-cushioned landing system, allowing it to operate just like a hovercraft over land, snow, ice, even water, and it can land more or less anywhere. The Airlander 50 will be commercially deliverable in the early 2020, HAV states.

With an eye on the lucrative air freight market, the potential for airships transporting heavy loads hasn’t been missed by other players in the market, including the US defence giant Lockheed Martin which is working on a rival model. The firm recently revealed a prototype of its LMH-1 heavy lift airship in California, US.

When complete the 120ft (37m) long airship will be capable of carrying more than 23t of cargo along with 19 passengers and two crew. While in Russia work is underway to create the 130m airship, Atlant 100, which is expected to be able to carry 200 military personnel or as much as 60t of cargo at speeds of up to 86mph.

Experts say the time is right. The cost is attractive (the Airlander comes in at around £30M compared with about £250M for a typical airliner), concerns around climate change have justified another look, plus weather forecasts and materials are infinitely better than before. If these future airship projects hit the market, it could offer a whole extra dimension to construction site logistics.

Flight plans

Aircraft manufacturers around the world are developing prototype hybrid airships for potential special transport applications.

These include:

Hybrid Air Vehicles

Hybrid Air Vehicles is developing a hybrid aircraft, the Airlander, targeting the heavy cargo sector. They’ve recently completed assembly work on the first of these aircraft.

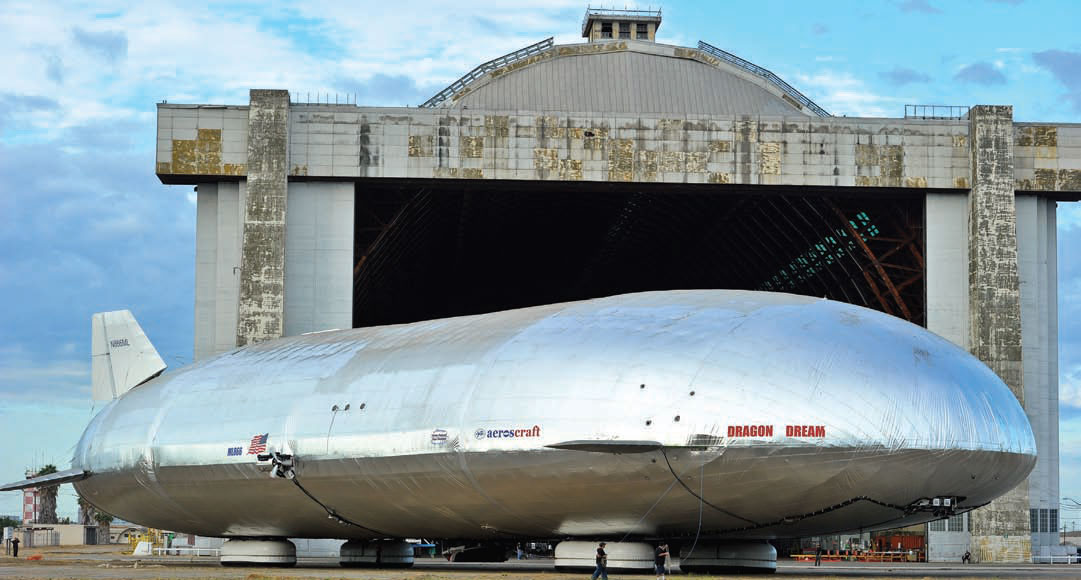

Aeroscraft

California-based Aeroscraft have recently tested the first prototype of its Dragon Dream. This is capable of lifting 66t, but the firm plan a larger version capable of lifting 250t.

SkyLifter

SkyLifter’s eponymous lighter than air vehicle is explicitly targetted at the crane industry. With a capacity of 150t, they believe it could be used not just for transport, but to install components on wind farms and similar.

Lockheed Martin

Lockheed Martin is developing a hybrid airship aimed at delivering cargo to isolated locations around the world. They will sell the airship through Hybrid Enterprises.