Local heroes

8 September 2011Stuart Anderson assesses the fortunes of local crane builders in Russia and the CIS since the fall of the Soviet Union

It’s been a tough 30 years for the Russian crane industry. With the fall of communism and subsequent financial crises, capital intensive industries were hit hard.

Russia’s leading mobile crane maker, Avtokran, is based in Ivanovo. By the end of the Soviet era the town was suffering from an unprecedented economic crisis. By 1999 Avtokran had made several times more mobile cranes than any other manufacturer in the world but was on the brink of bankruptcy. It wasn’t just that the economy was in desperate condition, but during Soviet times Avtokran had been required to carry the cost of local hospitals, sanitariums, clubs and social facilities.

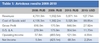

At the start of the decade it had been employing close to 6,000 people. Like every Soviet crane maker, Avtokran was dependent for truck chassis on Russia’s automotive industry and limited in its potential for product development. At the start of 1990s its largest crane was a 14t telescopic with a two-section boom; by the end of the decade it was a 50-tonner. The enterprise was able to free itself of many of its local social infrastructure responsibilities and new life was breathed into the company. Since then the company stabilised and recovered before the financial crisis made 2009 very challenging, as shown in Table 1.

Although it has challenges ahead, it is clear that today Avtokran has a good chance of surviving, not least because last year the Russian oligarch Oleg Barinov—a long-term investor in the business— completed his acquisition of Avtokran and its Gazprom-kran subsidiary. Though still bound by the enduring out-dated culture of the Russian crane market and separation of the crane and crane carrier businesses, in recent years Avtokran has done more than any other Russian crane maker to create a more-integrated crane manufacturing business, through the association of Avtokran, Gazprom-kran and BaZ. In January 2011 JSC Avtokran appointed Evgeny Tokarenko as its new managing director. He joined from the smaller crane manufacturer Motovilikhinskie, based in Perm, and succeeded Nicholai Grigorievich Shchegolev who returned to his former position as head of sister company Gazprom-Kran in Kamyshin. Since then the results have improved dramatically, as shown in Table 2.

Through the development partnership between the Bryansk-based military and off-road vehicle specialist BaZ that dates back almost 10 years, a line of carrier chassis has been developed that feature frames integrated with the carriers. Compared to the traditional and still pervasive practice of attaching crane torsion boxes with outriggers on top of the truck chassis rails, i.e. in boom truck fashion, the integrated approach delivers lower weight, lower cost, lower height and superior outrigger configurations.

The tight and growing relationship between Avtokran, its subsidiary Gazprom- Kran and BaZ saw the group reduce its dependence on ‘commercial’ truck makers, and facilitated development of larger cranes. BaZ’s carrier development began with lower-volume cranes of 50t and greater built by Gazprom-Kran, but has moved down the size scale. Although BaZ developed 25t 4x4x4 and 50t 8x8x8 all terrain carriers as well as conventional truck crane carriers, it’s clear that the truck chassis have proved the most successful.

Chinese suppliers and rivals

In an effort to reduce manufacturing costs, BaZ moved away from domestic components and chose Chinese Cummins engines as well as Chinese axles. Increasingly close ties are being made between the Russian and Chinese automotive industries. It’s a trend extending to crane components, with Chelyabinsk proudly proclaiming at CTT 2011 the use of (some) Chinese parts in the upper of its new KC-55733 32t truck crane.

Recent years have seen technical development in mobile cranes in Russia and the CIS, but at nothing like the pace and scope in China. The fact that 90% of the total market for truck cranes in Russia and the CIS is concentrated in the 16–25t capacity class, that this is contested by a dozen manufacturers and that these only produce the upper should facilitate the development and production of worldleading products. Historically this did not happen due, in large part, to local market demand and culture. Capital cost—rather than specification, performance or quality— has long been the dominant consideration.. In 2009 Ivanovets introduced one of the most advanced 16t and 25t truck cranes ever produced in Russia—the AK-16 and AK-25. Yet in 2010 the leading manufacturer with a total market share of 50% only sold “over 100 units” of these, its premier less than 10% its total volume in size classes and illustrating the continuing market ‘preference’ for lower-spec/lower cost models.

What Russians want

Generally speaking the performance standards of domestic cranes are significantly inferior even to Chinese cranes. Most booms in these smaller size classes are simple rectangular designs, with three or even two-section design, and many are sold with no jib extension. Average boom length for 25t truck cranes that account for nearly 75% of total unit sales is only around 21m, although models with four-section booms of 28-31m are offered by the leading manufacturers.

It’s only a decade since domestic 50t truck cranes became a factor. More recently, larger three-axle truck cranes in the 32–40t class and four-axle cranes in the 50–80t class have been developed by domestic manufacturers. An indication of the limited demand for ‘larger’ truck cranes is the fact that Russia’s second largest crane manufacturing group, Kudesnik— which includes Galichanin and Klintsy— only extended its line up to a 50t crane in 2007. Two years later Kudesnik proudly reported the sale of its 20th unit and then claimed that it was the sector leader in 2009. From this size-class upwards, imports outsell domestic products.

In terms of boom length, four-section booms of 30–34m length for cranes of32t–60t capacity are about the limit for the domestic industry. Russia’s first fivesection boom (of 37.8m length) was introduced by Avtokran on its 40t Ivanovets KC-54713 just two years ago. Longer boom lengths is part of the appeal of Chinese truck cranes (Chinese 25-tonners have booms of between 23 and 38m length). In Russia, the use of high strength steels and rounded boom profiles is a very recent development still generally limited to selected larger or ‘premium’ models. While more comfortable rounded cabs offer joystick rather than long lever controls, the older, lower-cost designs remain dominant.

The largest telescopic boom crane manufactured in Russia remains the 100t Ivanovets KC-8973 manufactured at the Gazprom-Kran plant in Kamyshin and mounted on a MW-8973 10x8 all terrain carrier. Introduced in 2002, the crane features a four-section boom that is just 41.4m long (+15m jib)—compared to the 60m seven-section booms available with the leading European 100-tonners. However the most popular Russian all terrain is the 50t Ivanovets KC-6973 mounted on the BaZ 6909.8 8x8x8 carrier. By 2009, around 40 had been sold, with Russia’s Ministry of Defence a significant buyer since 2005. Last year OAO FSK EES, the enterprise responsible for Russia’s power grid, ordered 17 of the 50t units.

All of the leading crane manufacturers offer their machines on a variety of trucks of different makes that include very lowspec/ low-cost units. For example, some 25t capacity cranes are not just offered on a choice of 6x4 and 6x6 but also on 4x2 wheel drive carriers. There remain six significant carrier makers (three Russian, two Belorussian and one Ukrainian) offering just two all terrain carriers (80 and 100t class) and some 32 different model series from two to four axle truck carriers with numerous specification variations. Russia’s largest automotive manufacturer, stateowned KamaZ, is the dominant supplier of truck crane carriers with twelve base models up to 60t capacity, and is the only manufacturer present under all brands.

While the drawbacks of using commercial trucks as crane carriers are clear, the benefits of parts support, widespread service networks and operator/mechanic familiarity are persuasive. Many of the trucks are very old designs, but these products have been tried and tested in the extraordinarily harsh climactic and terrain conditions. A good example was the recent delivery of a 50t capacity Galichanin KC-65713-2 on a MZKT- 700600 8x4 truck that traveled 6,000km (4,000 miles) including 2,000km (1250 miles) across “impassable” cross-country terrain from the factory to the customer in the Verhnechonsky oil and gas deposits of the Irkusk region.

All indigenously produced truck cranes are offered with Arctic modifications, and many are available for work in temperatures as low as -60°C. Russian crane makers install double-glazed cab windows, double cab heaters, electric heating of fuel tanks, lines, engine block heating, etc. Russian truck cranes do tend to stand very tall but this facilitates very high ground clearance, which in deep snow and soft rutted muddy roads is a real plus.

Slow steps in Odessa

Ukraine’s crane makers continue to struggle to survive. Odessa-based Krayan was once the leading Soviet maker of larger-sized hydraulic cranes, selected by Soviet authorities to drive the USSR’s crane development and production plans. Starting in 1977 it produced some 2,300 cranes in partnership with Poland’s HSW (who provided the carriers). In 1988 it produced a 250t 8-axle truck crane resembling the Grove TM 2500 that still today is the largest hydraulic crane ever made in the former Soviet Union. It was then engaged in the ‘Kranlod’ joint venture with Liebherr producing 50 and 70t RTs and ATs between 1987 and 1993. Both failed because of the lack of sustained investment in facilities, engineering development and component technology.

Still state-owned, Krayan is now in desperate financial straits. Ukraine’s president has been involved in thus-far unsuccessful attempts to find a private buyer. For years Krayan’s production had been running at very low levels and it is many years since this once famous enterprise developed a new crane. Meanwhile, in recent years, Ukraine’s other two mobile crane makers have been sold into private hands. The largest crane maker, Drogobych, which has produced over 70,000 telescopic truck cranes, was sold to Cyprus-based investors at the end of 2009. Similarly, the smallest truck crane maker JSC Strela was purchased by HMC Industry—a real estate development and investment company in 2006.

With domestic truck crane production reaching 700 units in 2007, shortly after buying Strela, HMC announced plans to invest $3m to boost its output that had accounted for less than 10% of domestic truck crane production. After many lean years Drogobych (DAK) was the big winner producing 636 truck cranes in 2008. The financial crisis saw demand collapse in 2009 with only 150 units of DAK truck cranes produced and 118 of these exported. Demand recovered last year, though not to recent levels, but Drogobych hasn’t been idle.

DAK has displayed a heightened level of innovation, becoming the first to use a “non-Soviet” truck in the shape of the Ford Cargo 3430D under its 28t KTA-28. More recently in June DAK introduced its largest model to date, the 50t KTA-50, featuring a five-section 36.5m ovaloid boom made from high grain DOMEX S700 steel that is the longest boom in its class made in Russia/CIS. The KTA-50 is offered on a choice of 8x4 and 8x8 wheel drive Russian KamAZ and Belorussian MZKT trucks, and features the quality of Parker hydraulics and Sauer-Danfoss electronic controls, as well as radio remote control.

Made in Minsk

This year the Minsk Automobile Plant (MaZ) celebrates 60 years since its MaZ-200 4x2 truck was developed as the base for the first 5t capacity Soviet lattice crane. MaZ became a huge producer of small trucks, including tens of thousands of truck carriers as bases for various types and makes of lattice and telescopic cranes. In 1991, MaZ was ordered to create a separate division named Minsk Wheel Tractor Plant ‘MZKT’ to manage its special vehicle division. By that time MZKT was producing special 8x4, 6x6, 8x8 AT and truck carriers for service with 50 and 80t telescopics manufactured at the Krayan plant in Odessa, Ukraine and the Sokol plant in Samara.

In February 2005, on the order of the President of Belarus, MaZ assumed control of the Mogilevtransmash crane and equipment manufacturing enterprise, along with its 2,600 employees, due to its financial difficulties. Based 180kms (110 miles) from Minsk in the town of Mogilev, the enterprise made its first 15t telescopic crane in 1993 and naturally mounted it on a MaZ truck. Since then Mogilev’s crane business has prospered with production rising to 562 units in 2007 and to 700 in 2008 before dipping relatively moderately to 535 in 2009. 2010 proved a difficult year for MaZ and Mogilev but business has recovered sharply in 2011.

Last November a prototype of Mogilev’s largest crane to date—the 40t capacity KC- 6571BY—was developed, featuring a new rounded profile boom manufactured from fine grain Weldox steel. Mounted on the new MaZ 6903 6x6 carrier, introduced to coincide with the 65th anniversary of MaZ, the 250hp truck has an integral crane frame and outriggers allowing an overall lower profile. Unusually amongst Russian crane carriers in this size class, it features large single tyres all-round and has anti-lock brakes. Since May, MaZ and Mogilev have reorganized their operations with production of cranes, aerial work platforms, concrete pumps, etc being concentrated at the Mogilev plant. Unlike its competitors, MaZ has the benefit of being both a crane and a large-scale automotive manufacturer, offering the potential to develop trulyintegrated and competitive products.

There are a few other rays of light. For many years, the crawler crane has been largely-ignored by Russia’s crane makers. In Soviet days, East Germany’s Takraf/Zemag Zeitz supplied thousands of its 25–63t capacity heavy duty crawler cranes to Russia and Ukraine. That ceased in 1990, but many of these very old cranes are still in service. Such is also the case for Russia’s leading crawler crane maker, Chelyabinsk Mechanical Plant (CMZ), who has recognized the potential replacement market. At CTT 2010 CMZ introduced the 40t capacity DEK-401 diesel-electric crawler crane. Although the manufacturer professes to be satisfied with its reception, so far monthly output is only running at 1-2 units. Nevertheless CMZ has now been joined in this sector by the first lattice crawler cranes from Klintsy—a 36-tonner designed in Germany—and from Ivanovets (a 50-tonner). However, intriguingly, Ivanovets is now also planning its first tele boom crawler crane, a 100-tonner.

Further diversification has been seen, with Ivanovets branching into knuckle boom loaders, while Klintsy has moved into the tower crane sector through license and marketing agreements with Italy’s G.C. SpA, a former licensee of Peiner that still employs this eponymous trademark.