Decades of Evolution

5 August 2021100-tonne all terrains - lighter, stronger, more reach and more compact - spoilt for choice! Stuart Anderson, President of Chortsey Barr Associates, reports on the evolution of the all terrain crane and the choices available today.

Over the years much has been written about the emergence of the all terrain crane and forecast demise of the truck crane. It is a story that had its beginnings in the early 1950s with the first small 4x4x4 all terrain cranes products developed by Thomas Smith & Sons (Rodley) Ltd for the UK Ministry of Defence and a few years later by Demag Baumaschinen GmbH with the cab-down ‘Krake’. The concept was commercialised during the 1960s and early 1970s by the pioneering efforts Leo Gottwald of Dusseldorf and then rapidly advanced by Harnischfeger P&H GmbH and Liebherr Werk Ehingen with the first two-cab 25-tonners.

All of those early ATs were essentially 4x4x4 Rough Terrains with increased travel speeds and improved suspension systems. etc. In those days as manufacturers entered a ‘new’ market they were keen to retain the main characteristics of the RTs – pick-and- carry lifting performance, travel control from the crane cab, compact dimensions and all wheel steer and drive. Until Harnischfeger P&H introduced its 25-tonne WS-250M in 1977, all terrain cranes were equipped with a single upper cab and it took until 1983 before a viable 4-axle AT in the form of Liebherr’s LTM 1060 arrived and radically changed the shape and future of the market. Even so, that development wasn’t driven by ‘normal’ developments in market demand – rather by the award of a huge contract from the USSR. By this time, even though the term ‘All Terrain’ was becoming an established new category and as larger ATs began to emerge, most of these so-called ‘All Terrain’ cranes retained the features common with Rough Terrains i.e. pick-and-carry performance, travel controls duplicated in the upper cab, etc.

However, those same market forces that had driven developments in small ATs had been more-widely recognized and applied to address the relatively poor off-road travel performance of truck cranes. The 1960s witnessed a global boom in demand for tele truck cranes that began with small cranes of 10-25-tons capacity and quickly blossomed into demand for ever larger tele boom cranes with longer and longer booms to replace traditional lattice boom cranes. Still, as tele boom truck cranes grew larger, they generally retained the design configuration of the lattice truck cranes they sought to replace. Of course, early designs of telescopic booms were very heavy compared to lattice booms causing significantly increased road weights of these cranes. In their efforts to limit GVWs and achieve legal axle weights and balance, manufacturers had to limit the amount of counterweight carried. Even with the application of new T-1 high tensile steels in the booms, lifting capacities still paled in comparison with those of the lattice boom cranes they sought to replace.

In a very crowded global market, the established market leading manufacturers – Grove, P&H, Coles and the emerging Japanese makers Tadano and Kato – struggled to out-do each other with conventional design approaches. At the same time the race was on to build ever-longer and stronger tele booms. However, more radical innovations had not completely ceased. Up until the 1960s, the crane makers of Germany were relatively unknown outside of central Europe. Indeed with the exception of the afore-mentioned internationally-established players, there was relatively little export activity amongst the scores of smaller-sized European makers. Like many others, while the likes of Gottwald and Demag had become design leaders in their home markets, they had generally failed to establish themselves in the broader international market. But while these important German manufacturers lacked international sales and marketing, their technical goals were set very high. Certainly, they couldn’t compete on price or global marketing but as telescopic boom cranes reached 75 and then 100-tons capacity the German manufacturers discovered a real opportunity to leverage their technology.

Leading the charge were several inspired crane designers whose names would be writ large in the annals of mobile crane design and development: Peter Eiler (Gottwald, Krupp) Rudolf Becker (Gottwald, Demag and Liebherr Werk Ehingen), Dirk Kelp (Demag), Helmut Blasé (Krupp and P&H GmbH), Heinz Heyer (Coles Krane), Dieter Jurgens (Harnischfeger, Century II, & Deep South) and Hans Weiskopf (Gottwald).

For the first time, 1973’s Hanover Fair saw a significant coming together of the fruits of the labours of this group of outstanding engineers. There, lined-up against each other, were Gottwald’s 75-tonne AMK 85-42 (introduced in 1971) Demag’s 75-tonne HC 200 (launched in 1972) and Coles Krane’s 80-tonne LH 800 (1973). Of course very few engineers or executives from abroad were present to seen the new threats. All of these cranes were notable for their compact five-axle carriers, 39-40m booms and 17.5-21m luffing lattice jibs. Even so, by then Gottwald had already made the next step with their 125-tonne AMK 155-53 mounted on a compact 10x6 carrier and Krupp would soon follow with their 120-tonne 120GMT. By this time, demand for larger telescopics was booming and even though the large U.S.- built Grove truck cranes were dramatically over dimensioned and over-weight vis-à-vis European regulations, enforcement was limited and crude. All across Europe market-leading Grove won numerous customers ranging from Schmidbauer and Richter in Germany to Sparrows in the UK to Sarens in Belgium. But that was about to change.

The key was balance. Since the emergence of heavy lattice boom truck cranes in the wake of WWII, road authorities had addressed such heavy vehicles with ‘consideration’. There were no simple solutions – pretty much all machinery was ‘heavy’ and road authorities had little in the way of product knowledge and power. Truck crane design had advanced rapidly and competition was intense. Since the days of the lattice boom cranes had been designed as integral working machines – as ‘ready-to-work’ as was reasonably possible. Counterweighting cranes had become standard practice since the 1930s and the counterbalancing weight applied to their rears had gradually increased. Basically all cranes were ‘tail-heavy’. Addressing this issue wasn’t a complex challenge but it flew in the face of the very concept of a ‘ready-to-work’ machine – it meant splitting the counterweight to allow that weight to be balanced across the length of the truck carrier.

While the term All Terrain was now being widely attributed to small 4x4x4 cranes, larger cranes continued to be named Truck Cranes. Getting larger sized tele truck cranes ‘onthe- road’ was a challenge for all local manufacturers but even more challenging for the American manufacturers. US road regulations were radically different from those in Europe and regulations differed from one European country to another. This situation opened the door for specialist makers of crane carrier chassis such as Faun, Foden, Saviem, Consolidated Dynamics, Mol and others who, for the next ten to fifteen years enjoyed a lucrative trade.

Meanwhile, step-by-step the leading European truck crane manufacturers such as Krupp, Gottwald, Demag, Coles Krane (based in Duisburg), Liebherr as well as Harnischfeger P&H GmbH and Grove-Allen (UK) were busy addressing their customer’s demands for similar features and characteristics now appearing in small all terrains. Here are a few selections:

- 1967: Gottwald AMK 85-42: 75t @ 3m; 39m 5-section boom, 8 x 6 Gottwald carrier: 10m long x 2.75m wide; 2-engine; 8t tele counterweight; twin 14.00 tyres on rear tandem and only 62 km/hr max road speed, 5-speed gearbox and conventional rear axle drive and front axle steering. SPECIAL FEATURE: Front axle drive & 5-section 39m boom.

- 1971: Krupp 80 GMT: 80t @ 2.75m; 39.15m 5-section boom; 10 x 6 Krupp carrier: 12.77m x 2.75m wide; Single 14.00 tyres; 8t removable counterweight; 2 engine ; 5-speed gearbox and two speed transfer case; 20m luffing jib. SPECIAL FEATURE: Single tyres all round; 2.75m wide carrier; Optional luffing jib

- 1977: Liebherr LT 1080 80t @ 3m; 40m 4-section boom; 10 x 6 x 6 with front axle drive and steer; 20m luffing jib; 11.17m x 2.75m wide Liebherr carrier; 6 or 12t tele counterweight; 2-engine; 6-speed gearbox and 2-speed transfer case (optional automatic transmission), 14.00 tyres (twins on rear); Coil spring suspension: SPECIAL FEATURE: choice of standard and heavy counterweight, Front axle drive and steer.

- 1981: Krupp 100 GMT: 100t @ 3m; 41.8m 4-section boom; 20m luffing jib; 12.9m long x 3m wide 10x6x6 carrier with front axle drive; Allison automatic transmission + 2 speed transfer case; 14.00 tyres (twins on rear); SPECIAL FEATURE: Standard automatic transmission.

- 1985: Demag AC 265: 100t x 2.7m; 45m 5-section full power boom; 8x6x8 (8x8x8); 10.63m long x 2.85m wide carrier, 16.00 singles all round; ZF power shift torque converter transmission + 2-speed transfer; Hydro-pneumatic suspension; Choice of 1.5t, 10t and 16t counterweight. SPECIAL FEATURE: First 100t on 4-axle carrier; Optional all wheel drive and steer, Range of counterweight choices; large single tyres all round.

With the exception of the Demag AC 265, all of the above cranes were marketed at truck cranes. Demag was the last of the leading German manufacturers to enter the all terrain segment but soon carved out its own ‘niche’ by radically changing the established norm with its various models being shorter, lighter and more-compact due to being carried on one less axle than their competitors. Demag had recognized that it was late to the party but soon made up for lost time. In a relatively short time, the AC 265 was largely responsible for establishing the Demag brand in Japan. After entering that market in 1987, represented by the large trading house C. Itoh, Demag soon establishing a strong position with some 50 of the 100-tonne units sold over the next three years. Similarly the manufacturer enjoyed significant success in the Soviet market selling some 45 AC 265s with -40-degree C GOSH ratings. Closer to home the AC 265 became one of Demag’s early successes in the UK market and became a major factor in getting Demag’s new Wallerscheid factory up and running successfully.

The biggest step forward in the growing dominance of the all terrain crane came in unusual fashion in 1990 when market-leading Liebherr announced it was ceasing production of truck cranes and committing wholly to ATs. In making this surprising announcement, Liebherr Werk Ehingen’s legendary CEO Freddy Bar fired an astonishingly bold shot across the bows of its erstwhile competitors: ‘The AT is the future!’. And indeed so it has shown.

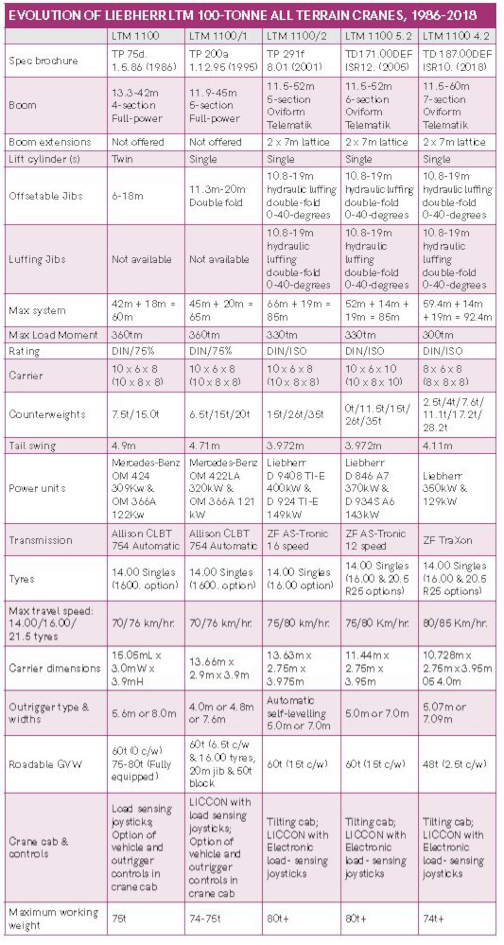

Our tabular analysis of five generations of 100-tonne class ATs serves to show the evolution of Liebherr’s line. By the time that Liebherr introduced its first LTM 1100 in 1986, a decade had passed since the manufacturer entered the 100-tonne tele boom segment with its 100-tonne LT 1100 truck crane. When the first Liebherr 100-tonne LTM 1100 emerged, Liebherr’s 100-tonne truck crane had already gone through several up-grades – with capacity increasing from 100 to 110 to 120-tonnes capacity but while its capacities had increased, it remained a relatively long 6-axle crane with a 45m four-section boom. Since its launch, the LT 1100 hadn’t been a trailblazer in the 100-tonne class. Indeed it followed a long list of successful 100-125-tonnetruck cranes made by Grove, P&H, Coles Krane, Gottwald, Krupp, Kato and Tadano cranes into the market.

Changing the game from the Truck Crane to the All Terrain turned out to be a marketing master stroke - largely putting the competition on the back foot. As our analysis shows, the first Liebherr 100-tonne AT offered a more compact five-axle option with a more flexible drive and steer configuration. Over these past 35 years the 100-tonne class has been one of the consistently most intensely-contested market segments. During these years several competitors have come and gone (Coles, PPM, Luna. Rigo, Krupp, Ormig, Gottwald, Pinguely, and others) but thanks largely to its constant product development, Liebherr has held onto the #1 spot. Today the manufacturer offers the market a choice of 4-axle (LTM 1100-4.2) and 5-axle (LTM 1100-5.2) models and most recently has refreshed its offering with the introduction of its very popular VarioBase asymmetric outrigger option, its ‘ECOdrive’ ZF Traxon transmission, ‘ECOmode’ fuel saving system adding to other now-well-established features such as BTT Blue tooth remote control and hydraulic luffing bi-fold jib. Neither should it be overlooked that the current 4-axle LTM 1100-4.2 offers more boom reach, more jib reach and stronger capacities than several of its much heavier predecessors.

However, lest from the foregoing we give the impression that in the 100-tonne class Liebherr is the only game in town – nothing could be further from the truth! In recent years both Grove and Tadano-Faun have developed extremely competitive four-axle ATs in the 100-tonne class. In several key respects Grove’s GMK 4100L-1, Demag’s AC 100-4L and Tadano’s ATF 100G-4.1 are very similar: 8x6 wheel drive, Mercedes Benz 320-340kW carrier diesels, 60m 6 or 7-section booms and very long hydraulically-luffing bi-fold jibs. One interesting business approach by Tadano is to employ the 120-tonne boom and upper of its new five-axle ATF 120G-5 on its new four-axle 100-tonne sister machine. In our experience such ‘apparent’ economies also come with their own pitfalls.

Fundamentally the key difference between the 100-tonners is that the Grove is a single engine crane while Tadano and Demag have chosen to perpetuate the argument in favour of a two-engine set-up by installing a 129kW upper diesel. Of course the jury is still out on this subject but most manufacturers are neither completely wet or dry on the issue and we hear very few loud customer protests in favour of one or two diesels. Meanwhile manufacturers continue to claim that their approach offers greater benefits in terms of fuel consumption, emissions, etc., etc. Bottom line to date is that both single and two-engine cranes of various brands continue to sell well!

While in certain markets Chinese cranes have made an impression, in the developed markets of Europe, North America, Japan, and Oceania, crane buyers have access to a truly impressive range of European ATs. It is no exaggeration to recognize that the range of choice offered by Liebherr is truly outstanding in its breadth and quality and not only by today’s standards but by those of any time in the history of the mobile crane.