“More people are killed through electrocution when working with cranes as a result of contacting powerlines than any other cause,” says Jim Headley, president of the Crane Institute of North America and author of the Mobile Cranes Handbook. His book uses the relevant ASME and OSHA standards as a basis for a section entitled “Working Cranes Near Powerlines” which uses diagrams and simple terms to provide clear and useful advice to operators. “Normally it is not the operator that gets electrocuted it is someone working around the crane,” he adds.

A crane that hits a powerline will become energised itself but as the cab is made of conductive material the electricity flows around the operator who remains safe. This phenomenon was first observed by the scientist Michael Faraday in the 1830s. “The guy in the cab is in a metal box, a Faraday cage, so he is OK. But if he tries to jump off and holds on to the crane he will probably burn his arm or leg off,” explains Hugh Pratt, secretary of CPLSO (Crane Power Line Safety Organisation) and inventor of the Insulatus insulating link product. “The ground under the crane may be at 20,000V but five metres away the voltage is zero and so the area of ground between the two is energised with a potential difference.”

Anyone on site that is standing close to the crane such as a rigger, spotter or other worker could be electrocuted by the current flowing through the energised ground. This occurs if they move or rush toward the crane to try and help. “As you stride across the energised ground one leg could be at 5000V and the other leg at 12000V. It would stop your heart by ventricular fibrillation,” explains Pratt.

In his book, Headley spells out the emergency procedures for moving away from an energised crane reminding operators that this is a last resort in the event of emergency. The operator should remain in the cab until the lines have been reenergised, however should it be necessary to leave for example as a result of the crane being on fire, then operators are advised not to climb down but to jump ensuring that they are not touching the crane as they fall. Moving away from the crane should be done as a shuffle – lifting and placing one foot away from the other is enough for the body to experience the potential difference in the ground.

This of course is the worst case scenario, as is any crane touching a powerline. Guidance from both OSHA and the ASME is carefully written so as to ensure that cranes do not get anywhere near the live cables. Avoidance is the objective. If lines cannot be de-energised then the guidance requires operators to maintain a minimum distance from the line of 20 feet. Alternatively OSHA document 1926.1408 gives minimum clearances based on the voltage of the line. Under this guidance, the operator may work within 10ft of the crane if its voltage is 50kV or lower. Between 50 and 200kV the crane must remain 15ft away. Between 200 and 350kV it must remain at 20ft. This sliding scale continues up to between 750 and 1000kV where the minimum clearance required is 45ft. Above 1000kV a qualified electrical engineer must be called in to set the appropriate clearance which will depend on factors such as the line voltage, atmospheric conductivity, speed of equipment movement and wind speed.

If operators are working on maintaining a minimum approach distance to a live line then there is a series of other precautions that must also be taken to ensure safety. A planning meeting must be held with the site team to highlight the location and review the steps for prevention of encroachment. Any tag lines used to control the load must be non-conductive. Some type of encroachment warning system must be used. The most common of these is a spotter. “You have got to have a spotter or a signal person to keep the operator outside that clearance zone and that is his only responsibility, he can’t be doing anything other than that,” says Headley. As a former crane operator himself he points out that it is almost impossible for an operator to judge where he is in relation to the powerlines as the background, lighting and other factors can all affect the perspective of the driver. “Sometimes you think that the powerlines are way off from your perspective in the crane and they are close to you. Sometimes you think they are right on you and they are far away,” he says.

However, Pratt calls the effectiveness of a spotter into question. “The visual acuity required for determining the distance of 10ft is 20:13. This is significantly better sight than 20:20 which is normal vision. You might as well ask him to levitate as you just can’t do it. You can legislate against touching power lines, put up barriers, have spotters looking out for power lines, you can train people not to hit them but at the end of the day if you hit them you need insulation,” he says.

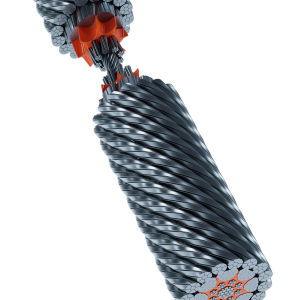

To this end Pratt has developed an insulating link which hangs from the crane hook and insulates the crane load from potential electricity protecting the rigger. “They are made of a steel chassis and a reinforced plastic insulation so it is very resilient. It is an engineering conundrum because you need the properties of glass for insulation and the properties of steel for strength.”

Use of the links however remains low as operators are not mandated to use them, but Pratt continues on the quest to stop the main cause of construction crane fatalities with his work at CPLSO involved developing and publishing industry standards.

Multiple choice

Not surprisingly a wide variety of cranes are used for work in the utility sector. These non-insulated cranes require operators to maintain the safe working distance.

North Carolina based utility equipment supply specialist MAP Enterprises Inc. say that their 25TM, 38TM and 50TM Effer knuckleboom cranes are highly popular among rural electricity cooperatives and investor owned utility firms. “They choose them because you have more versatility in tighter areas and you are able to get more capacities at a lower boom angle which makes a smaller footprint so they are more compact,” explains Allen Pittard, Marketing Manager at MAP Enterprises. “Contractors use them for new construction and the electricity companies use them for maintenance and refurbishment of their system. Sometimes we sell them with pole grabs, sometimes they are used with winches.

Sometimes they are used with personnel baskets,” he adds. The need to lift people as well as equipment led manufacturer Altec to invest in the creation of a dual-rated crane which meets both the requirements of ASME B30.5 for cranes and ANSI A92.2 for aerial lifts. “One of our tallest reaching models, the AC40-152S, is a dual-rated unit. This means that it has two ratings, a crane compliant operation mode, based on set-up and configuration, and an aerial compliant operating mode, again based on set-up and configuration,” explains Dan Brock, Altec Cranes Market Manager. “The AC40-152S when configured as a crane to lift and move suspended loads has a maximum capacity of 40USt with a main boom of 152ft that can be increased with the optional 49ft telescopic jib,” he says. “When configured as an aerial, this machine has a quick-attach platform with 1,200lbs of capacity at all boom extensions and jib lengths. When positioning personnel at height with the machine configured with all optional jibs, the operator can work at a height of 222ft above ground.” Altec launched its dual rated crane in 2014 and was the first manufacturer to do so.

“By having one unit that can do multiple jobs, the company doing the work is afforded the benefit of reducing the number of trucks needed at any one location. As a result, the jobsite is less congested and companies can reduce fuel and maintenance costs associated with having fewer units,” says Brock.

To improve safety Altec recently released a new radio to control the unit at height. This radio has a full color display that shows the information from the Load Moment and Area Protection System, Altec’s LMAP. This ensures that the operator in the platform is working within the safe parameters of the unit based on its aerial configuration.

Other units for de-energized transmission construction include Altec’s AC45-127S, a 45USt machine that can be specified as a dual-rated unit, and the AC38- 127S.

However not all manufacturers are convinced of the benefit of dual rated machines.

The Elliot Equipment Company in the US manufactures customizable truck mounted work platforms and boom truck cranes with the HiReach and E-Line aerial platforms, along with its boom trucks all used in the utility sector.

“Elliott work platforms have capacities up to 1,200lbs, providing enough room for two workers, tools, and materials to reach the work area with one machine,” says Cara Eccleston, marketing coordinator for Elliott.

“Our platforms can be outfitted with hydraulic tool circuits, material handling, rotation and ultra-smooth proportional controls.”

The firm has been manufacturing work platforms since 1948 and has made them highly adaptable with customisation options such as special boom lengths, platform designs, insulation options up to 500kV and more.

In terms of safety the manufacturer offers a number of precautions. “Elliott’s EZ Crib outriggers offer 28in additional ground penetration, greatly reducing the need for handling heavy cribbing both in machine set up and tear down,” says Eccleston.

It also has a load moment indicator system, radio remote controls with built in information screens to show boom length and angle as well as fiberglass jib extensions. Anemometers to measure wind speed are also available on certain models.

Australian energy

The Australian standard for working near powerlines is AS2550 – Cranes, Hoists and Winches – Safe Use but each of the seven states have their own regulations that operators must adhere to. Like in the US there are also different rules for qualified electrical line workers who may operate under different legislation that may for example allow closer working distances.

“Electrocution through cranes hitting powerlines is an on-going concern in Australia. Often these incidents occur when smaller vehicle loading cranes – that are used to deliver building materials to site such as timber and steel – contact overhead powerlines that run down most of our streets,”

explains Stephen Holmes, owner of GTK Training PTY Ltd, a member of the Crane Industry Council of Australia. “But these incidents aren’t restricted just to vehicle loading cranes. Large cranes fall victim to powerlines on construction and mine sites throughout our country,” he says. Generally, on construction and mine sites in Australia good safe work method statements and hazard risk assessments are prepared prior to any lift, says Holmes, with powerlines a major consideration in these assessments. “However, incidents continue to occur which shows still more needs to be done,” he says.

Like in the US, a wide range of cranes and elevated work platforms are used for powerline work. Cranes used range in size from vehicle loading cranes of around 10tm size and bigger, up to large slewing mobile cranes used on high voltage power lines. Often large cranes are used more for their reach than capacity.

But large capacities are sometimes required for large transformers. “At times, we use non-slewing articulated pick and carry mobile cranes such as the Terex Franna for certain work. We also use cranes that are specifically designed for erecting and maintaining our powerline infrastructure,” says Holmes.

Typically, these cranes may have borers attached to the boom so the crane is a one stop shop for erection of poles. They can bore the hole, then erect the pole and all the hard ware such as cross arms and transformers that may be attached to the poles. These cranes are not insulated says Holmes pointing to models from Australia’s Premier Proline Limited as an example of this type of machine.

EWPs are very commonly used in the maintenance of powerline infrastructure. These are normally insulated to allow work on live lines. Most commonly they range in size from 8m up to around 20m, but bigger ones are also used.

Powerline workers are trained and authorised to undertake the work and use an array of specialist equipment including special insulated rigging components and tag lines. They also use specialist personal protective gear such as insulated gloves. It is a very specialist area that requires much training to allow the work to be done safely. Although these operatives use their own cranes, they sometimes bring in larger cranes and crane operators who are not specifically trained and so must operate under the direct guidance of the authorised workers.