When Hans Liebherr was designing the tower crane inside an American prisoner of war camp more than 50 years ago, little could he have guessed that his creation would not only be used to rebuild war-torn Europe but also find some unique applications elsewhere. Like in America’s pulp and paper industry, for example.

One such application involves three chip mills near the Oregon Coast, each owned and operated by Coastal Fibre Inc of Oregon.

At each site, stationary JC-40 Le Tourneau tower cranes – pedestal mounted, dockside style – are being used to unload log trucks and deck the logs or feed them directly into the chip plant. When no trucks are unloading, the cranes make picks from log decks, dropping their loads on to belts that feed the debarkers.

Why use tower cranes to ferry logs around instead of the traditional wheeled or crawler-mounted log loaders? For several reasons, says Coastal Fibre owner Bub Wilson.

Perhaps the most important is the savings that he is achieving in the cost of energy. Wilson says it costs only $500 a month for the electricity to run each crane, while the cost of diesel fuel for the log loaders at each site can run as high as $2,000 a month.

As for maintenance, Wilson says that not much is required compared to wheeled machinery. With tower cranes, Wilson does not have to pave over or continually grade the damp, muddy yard floor so that the log loaders can manœuvre.

“I was spending a lot of money re-grading and re-rocking the yard on a yearly basis to keep us out of the mud. And even when you pave the yard you contaminate your bark and just make a big mess. So I thought using a crane where I can unload, feed the plant and do the decking made a lot more sense. I have become more and more a believer.” Yet another advantage to the tower cranes, one that has become more evident in recent times, is that they are more environmentally-friendly than wheeled or crawler loaders, which can chew up the yard floor.

“They keep the yard cleaner, and with all the environmental issues and water run-off that we’re looking at in the future, I can’t even imagine using shell loaders anymore,” Wilson says.

One drawback to the tower cranes is that it is difficult to find qualified operators. But Wilson has solved the problem by sending new prospects to a “tower crane school”, which is conducted at his plant in Toledo, Oregon by the operator stationed there.

As for day-to-day maintenance, operators at each site learn how to service the cranes through the Le Tourneau distributor located just east of Portland, Oregon in Troutdale on the Columbia Gorge.

Wilson became interested in using tower cranes to move logs several years ago and bought all of his cranes on the used market. He says the use of tower cranes in southern mills is more common.

Two of his JC-40s are operating just a few miles inland from the Oregon coast, while the third is located at the active shipping port of Coos Bay, where both raw and processed logs are put aboard vessels sailing for Pacific Rim countries.

All three Le Tourneaus are working pretty much under the same conditions and specifications. Jib length on each is 100ft to 125ft (30m to 38m). All are operating at roughly the same height-under-hook of 85ft (26m). Logs are stacked as high as 42ft (13m) so there is plenty of clear space.

Travis Hunt, plant manager and part time crane operator at the Willamina, Oregon plant, says that it took less than a week to erect the JC-40. The crane went up in five sections: foundation, lower tower, main tower, A-frame tower head, jib and counter jib.

The foundation, which extends below ground, consists of more than 30 Douglas fir timbers driven into the ground and interlaced with rebar. The infrastructure was then flooded with cement.

At the Willamina plant, which is near where Keiki the whale (of Free Willy fame) was penned while in the USA, the JC-40 can unload between 18 and 20 log trucks a day, says Hunt. Each truck has a net capacity of between 65,000lb (30t) and 70,000lb (32t).

The logs being moved around range in length from just a few feet to 42 ft (about 1m to 14m). Average size is 36ft (11m). Most of the timber is of the Douglas fir variety that dominates the Oregon coastal range, but a good percentage of hardwoods, like Western red alder, also comes into the plant for processing.

Although most of the logs that are destined to end up in the chipper are smaller diameter ones, harvested during commercial thinning operations, every once in a while the JC-40 is called on to pick a huge old-growth Douglas fir or Sitka spruce from a logging truck and spot it for the log loader. Because of disease or defects, these logs have no commercial value as saw or plywood stock.

Jim Oostman, who works in Le Tourneau’s service department in Troutdale, says that all three cranes used in the chip mills were made in Longview, Texas. Brand new, the JC-40 costs in the neighbourhood of $1m.

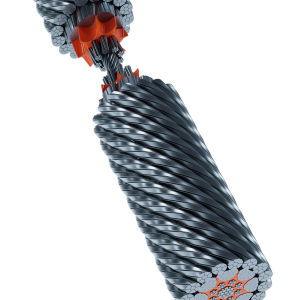

Unlike most lattice-structured tower cranes, the business end of the JC-40 is perched atop a hollow steel tube 3.6m (12ft) in diameter. The walls of the tube are three quarters of an inch (19mm) thick. The crane has a set of slip rings so that it can revolve without any worry of cables winding up.

Oostman says the only time Le Tourneau service specialists are called onto the scene is when the mills run across a problem they cannot solve. That happens about once a year.