The new crane has its roots in one of Piet Stoof’s earlier game-changing innovations with Mammoet, the MSG 50. Unlike other very high capacity cranes of the time, this was designed to be shipped in containers, allowing the company to bring heavy lifting capabilities anywhere in the world.

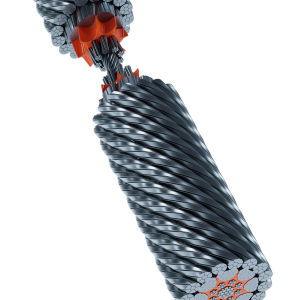

When Stoof first explained the concept that would become the Focus in 2013, ease of shipping was again key. The new system wouldn’t use pre-assembled latticework sections, but would be shipped as chords and struts, designed for easy assembly by local staff. By not shipping air, as happens with pre-assembled welded boom sections, transport could be made even cheaper.

More importantly than cutting transport costs, this approach opens up a much more significant customer benefit: vastly higher lifting capacity than is available with standard crane designs, as the boom can be assembled to any dimension, close to the crane carrier.

Helmens says, “In the past, container size limited mast section size to 2.4m or 4.8m. The new concept lets go of these fixed dimensions. Sections of any volume can be created, such as 8m or more, while still shipping in containers.”

Stoof’s first draft of the design pictured boom and back mast as two equally-sized A-frames, with a counterweight mast linking the back mast to the counterweight. This approach maximised capacity, into the tens of thousands of tonnes, and was key to assembly. The counterweight mast would pull up the two A-frame booms; when fully vertically erected, they would move apart for lifting.

The latest version of the concept brings a new approach, the Y-configuration. In this system, Stoof explains, capacity is not as high, although still well above 2,000t, but the crane can be assembled and used in much more restricted spaces, like refineries or inner cities.

Key to the Y-configuration is its vertical ‘ladder’ assembly. Here, front and back boom are single square pieces, rather than A-frames. The base of the crane is assembled with the initial sections in place. Then, the front boom section is pulled up while the back mast section remains fully connected to the carrier. Subsequently, the back mast section is pulled up while the front boom is connected to the carrier. In this process, the crane remains completely stable throughout assembly, with no work at height and no need to lay the boom down.

The new approach brings another key innovation: a special pivot section that converts the boom hydraulically into a luffing jib. On a normal crane, fitting a luffing jib will require laying the boom down, assembling the jib, and raising it again.

In the Focus, the boom can be used at full capacity, with the jib converter in place. The converter can be fitted wherever it is needed, according to the length of jib that will be required. In this way, the Focus can add a luffing jib at the flick of a switch.

Taken together, Helmens explains, all of these innovations mean that a 30,000tm luffing jib crane can be assembled in a very confined space: as little as 22m x 22m. A job that might normally require six weeks of costly downtime could see this cut to two weeks. In principle, he adds, the crane could be configured for capacities over 275,000tm.

Four years after Stoof first described the idea to Cranes Today, Mammoet are very much ready to go. As part of the design process, Mammoet and Stoof have met with oil companies—it was these talks that lead to the development of the Y-configuration. Bringing this idea to reality now waits only on the company signing its first contract for its use.

The development of the Focus highlights the different approach taken by integrated heavy lift, special transport and project engineering firms like Mammoet, compared to serial crane manufacturers. They can, as Stoof says, “Make the crane you need for the job, rather than you choosing the crane you need.”

An animation showing the assembly process for the Focus in its Y-configuration can be seen here