A Circuit Court jury in Milwaukee, Wisconsin awarded $99.25m damages in the Miller Park accident trial and found Mitsubishi Heavy Industries of America 97% negligent, writes Kenneth Lamke.

The jury found Lampson International only 3% negligent and decided all contract disputes between Mitsubishi and Lampson in Lampson’s favour. That means, according to Lampson attorney Don Carlson, that Mitsubishi will have to pay Lampson’s share of the damages.

Mitsubishi and Lampson were being sued for negligence by the widows of the three ironworkers killed on 14 July 1999 during construction of a new baseball stadium for the Milwaukee Brewers.

Of the $99.25m, exactly $94m is a punitive damage award levied against Mitsubishi.

The remaining $5.25m is compensatory damages for the loss of companionship suffered by the widows of the three ironworkers killed in the accident and for the pain and suffering of their husbands.

Lampson’s 3% share of the $5,250,000 would be $157,500, but will be paid by Mitsubishi, according to Carlson.

Jurors told reporters after the verdict that they assigned 97% of the blame for the accident to Mitsubishi because of numerous unsafe practices at the job site but mainly because Mitsubishi failed to have wind-sail calculations done.

Jurors said Lampson was 3% negligent because the firm did not give the three men who made up the Lampson crane crew enough authority to deal with Victor Grotlisch, the Mitsubishi site supervisor.

Mitsubishi attorneys declined to comment, nor would they confirm that they planned to appeal. They did tell Circuit Judge Dominic Amato that they would not waive their right to the standard amount of time, in this case to 28 December, to file so-called motions after verdict. Such motions must be filed before an appeal can be made.

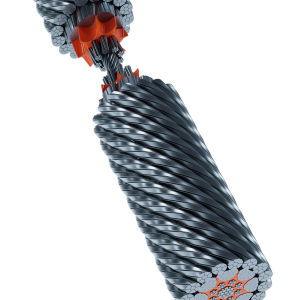

During the seven-week trial Mitsubishi and Lampson each sought to blame the other. At issue was who caused a Lampson Transi-Lift 1500-3A – nicknamed Big Blue in Milwaukee – to collapse while lifting a 450 US ton roof section in high winds.

The crash killed three iron- workers – William DeGrave, Jerome Starr and Jeffrey Wischer – who were suspended in a manbasket from another crane. It also caused $100m in damage at the site and delayed the ballpark’s opening a full year.

The $100m in property damage was not as issue in the trial because it was covered by insurance obtained by the local stadium board, which oversees the largely taxpayer-financed project.

Dramatic videotape of the crane collapsing was taken by federal safety inspectors who happened to be at the site on the day of the accident and has been shown repeatedly on local television news and at the trial.

Taken from a vantage point outside the stadium, where the Big Blue crane was also sitting, the tape does not show the collision of the crane with another crane inside the stadium from which the manbasket was suspended, or the subsequent free fall of the three men as they plunged 75m to the ground.

Mitsubishi holds the $47m subcontract to build the roof. Lampson leased the crane and a crew to Mitsubishi for $3.1m under what Lampson officials described as a bare lease, giving Mitsubishi full control of the equipment and the crew.

Mitsubishi and Lampson have filed cross claims against each other and their attorneys sought to portray the other in a bad light at the trial.

Mitsubishi claimed the crane was assembled incorrectly and that it was up to the Lampson crew to operate it safely. Lampson said Mitsubishi was in charge, ran a sloppy job site and ordered the fatal lift.

General contractor on the project is HCH Joint Venture, a consortium consisting of Huber, Hunt & Nicols of Indianapolis, the lead firm; Clark Construction of Chicago; and Hunzinger Construction of Milwaukee.

After the accident, Mitsubishi replaced the Lampson crane with Van Seumeren’s Demag CC 12600, which completed the last 30 roof lifts without incident, topping out on 15 November.

The widows contend that Mitsubishi, through its site supervisor Victor Grotlisch, negligently allowed the roof lift to be made in conditions that were too windy.

John Peterka, a wind expert for Lampson, said that at the time of the accident winds were 17mph to 21mph (27kmh to 34kmh) at the height of an anemometer mounted on the crane’s mast, about 180ft (55m) above ground – the same wind range reported by the Lampson crew.

But winds were gusting from 26mph to 33mph at that height, Peterka said. And at the height of the roof piece itself, about 254ft, winds were steady at about 23mph and gusting to 36mph, said Peterka, vice-president of Cermak Peterka Petersen Inc., wind engineering consultants at Fort Collins, Colorado.

Peterka said he did computer modelling that transferred National Weather Service data from the Milwaukee airport to the ballpark construction site a few miles away. Numerous other wind estimates were made during the trial by constructions workers, civilian sidewalk superintendents and one TV weatherman, all of them estimating winds in the 20s and gusts in the 30s.

Even more damning was the testimony of Howard Shapiro, chief expert witness for the widows, who said that the lift should not have been made on the day of the accident in winds above 11mph.

New York-based Shapiro, a noted industry expert, said that no one at the job site did wind-sail calculations to determine the effect of the wind on the load being lifted.

Both Mitsubishi and Lampson officials relied only on Lampson’s load chart, which specified that the crane could be used in 20mph winds, while ignoring the load chart’s direction that the effect of wind on the load also needed to be taken into account, Shapiro testified.

Shapiro accused Grotlisch, the Mitsubishi site supervisor, of playing Russian roulette with workers’ lives at the job site – a comment which the judge, with the jury out, later said that he agreed with. That led Mitsubishi attorneys to ask for a mistrial, but the judge declined.

Both Mitsubishi and Lampson witnesses have testified that they believed the other firm was doing wind-sail calculations.

As to why they did not stop the lift given the winds, Lampson employees said it was Mitsubishi’s Grotlisch who ordered the lift and that they had been conditioned not to disobey him because Grotlisch had, only a month before, forced the removal of the first crane crew supervisor supplied by Lampson. Grotlisch and that supervisor, Milo Bengtson, had clashed repeatedly over operational and safety decisions, the court heard.

Bengtson testified at the trial that Grotlisch had no common sense whatsoever. For his part, Grotlisch testified that he believed the wind was only 15mph to 17mph at the time of the accident – and still believed it as he testified.

But Grotlisch admitted that he ‘dropped the ball’ in not having wind-sail calculations done.

You had no idea on 14 July what effect wind would have on that load or how it might affect the crane, Grotlisch was asked by Robert Habush, who represented two of the widows. Correct, Grotlisch replied.

Grotlisch also maintained that, although he went to Mitsubishi’s trailer shortly after the accident, he never checked the firm’s weather computer for wind speed. At the pre-lift meeting on the morning of the accident, Grotlisch had told all the workers involved in the lift that he would monitor the weather that day.

In his testimony, Grotlisch also admitted that Mitsubishi was $40m over budget on its $47m contract, and that roof erection was behind schedule at the time of the accident.

Lampson engineering technician John Bozung, who did the rigging drawings for the roof lift, said it was Mitsubishi, not Lampson, that decided to combine two scheduled roof lifts of 100 tons and 350 tons into a single 450 ton lift; decided to assemble the boom and mast at 540ft when such height was not needed for that lift; and decided to raise the roof piece over a higher point in the stadium than a lower one, when that also was not necessary.

Mitsubishi, through its chief expert, Charles Morin, pointed the finger of blame at Lampson.

Morin said that Big Blue was improperly assembled by virtue of having a half-inch bronze spacer installed in the king-pin assembly.

The spacer was the crane’s weak link, Morin said. Had a similar Lampson crane been used – one with a king-pin assembly that did not contain a spacer – the crane would have withstood the side-loading caused when the roof piece began to move in the high winds, he said.

Morin, chairman and CEO of Engineering Systems of Aurora, Illinois, is a veteran accident investigator, having been called in on last July’s Concorde crash and previous high-profile accidents such as the skywalk collapse at the Kansas City Hyatt hotel.

Lampson defended the spacer. Manufactured at its machine shop in Kennewick, Washington, the spacer was strong enough to withstand normal operations, its employees testified. They said that if the lift had been made in safe wind conditions, the spacer was strong enough to have held firm and the 12-inch diameter steel king-pin would not have split in two. Such spacers are commonly used in Lampson cranes without problems, Lampson employees said.

But Lampson did concede that the spacer did not appear on the drawings for the crane that it supplied to Mitsubishi, and that the spacer was inserted on site at the last minute at the request of a Lampson employee who decided the king-pin assembly did not fit snugly enough.

Also at issue between Mitsubishi and Lampson, besides who did what at the jobsite, were the provisions of their contract regarding liability.

Lampson contended that even if its employees were found to be negligent in the crane’s assembly or in failing to stop the fatal lift, the contract required that Mitsubishi assume liability since the crane was leased to Mitsubishi and the crew was legally loaned to Mitsubishi.

Mitsubishi attorneys tried to show throughout the trial that the Lampson employees acted as Lampson employees to some degree, having identified themselves as such and having been paid through the Lampson payroll.

But Lampson responded that the crane crew had to be paid through the Lampson payroll because the crew were union members and Mitsubishi refused to sign the Miller Park project labour agreement. In trial testimony, the Lampson crew that worked at Miller Park made it clear that they took their directions from Mitsubishi’s Grotlisch.

The federal Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA), which investigated the accident, levied fines totalling $539,800 against Mitsubishi, Lampson and a third firm, Dannys Construction, which supplied ironworkers for the project, including the three who were killed. Those fines are being appealed.

OSHA investigators said wind was the principal cause of the accident, although their findings were not allowed into evidence at the civil damages trial.

Dannys could not be sued by the widows because it was covered by Wisconsin workmen’s compensation law, which limits a firm’s liability to the provisions of the workmen’s compensation insurance programme.