Alongside the high rise banks, the freeway loops, the theatres and the palm trees of downtown Los Angeles, a building with a difference is rising. It is a new cathedral and the Modernist neo-Gothic structure is one of the most challenging in the city for its builders.

Not only is the Roman Catholic ‘Our Lady of the Angels’ a complex design with “scarcely a right-angle to be seen in its layout” according to structural engineer Bryan Smith, but it must also be built to exceptional standards of finish and decor. Essentially, it must last forever, or anyway as near to that as is humanly possible in West Coast terms “We are designing the building to survive for 500 years,” says Smith, who works for engineers Nabih Youseff & Associates. Most of the city’s structures are torn down after perhaps 30 years, partly because the fast-paced city just moves on and partly because it is not worth battling with California‘s notorious earthquakes.

“This structure will be shaken by hundreds of small quakes,” says Smith, “as well as several big ones, up to 9 on the Richter scale. That’s the big one, when the state slides into the sea.” All of which means unprecedented strength for the walls and columns and astonishing durability for materials, finishes and fittings. The mechanical and electrical installations, designed by the British consulting engineer Ove Arup, must equally survive, or be easily replaceable.

To deal with quakes the building will sit on sliding Teflon and steel bearings. Side walls will have a different kind of bearing, rubber and steel ‘springs’ to prevent the sliding going too far. Letting the building go along with the vibrations helps reduce otherwise fantastic amounts of reinforcement steel that would be required in the walls.

But even using such a ‘base isolated’ structure, reinforcement must be on a titanic scale, concrete cover thickness an exceptional 75mm, joints and transitions exceptionally robust. In places where water could pond during rainstorms, stainless steel is used against long term reinforcement corrosion, as it is for crack inducers in the concrete wall panels.

A host of other details are equally stringent, not least the finishes for the concrete which require exceptionally high standards. And since the design demands an unusual bronze colour, this is harder to achieve than usual.

The impact on construction work is partly to create unusually high and precise lifting needs in a tightly packed and busy 2ha site, many of which will be met by tower cranes, two large Liebherr ECH 316 models, supplied by Liebherr’s US distributor for tower cranes, Morrow Equipment. Mobiles large and small also come and go as required.

The new church stands inside one block of the city’s cultural district at Grand Avenue, an area of theatres, museums and galleries. “That means the spaces are relatively tight – for the West Coast anyway,” says Jamie Garcia of the contractor Morley Construction. “There is not much room to bring in mobiles.” Not only does the 100m-long cathedral sit on the one-block site but there is also a residence for the Bishop, a campanile or bell tower, and carparking facilities. The central part of the site will also be open space with fountains and a carillon of bells.

It may be cramped, but it is still a large site and the Liebherrs need a long boom to cover it, says Morley vice president Terry Dooley. The booms are 70m long; they can lift 3t at the tip or 12t at 22m radius. While Morley has used tower cranes many times before, says Dooley, it is unusual to need such long booms. “We find the cranes versatile and effective,” he says.

Dooley adds, though, that they still have to figure out the details of how to erect the roof beams. These are 3m to 5m deep steel trusses, skewed across the highest points on the walls which are up to 43m high. “It will probably mean hiring in something bigger when the roof goes on sometime next year,” he says, “but we still have to work out access.” However, the tower cranes are already working busily. Large amounts of steel must be carefully positioned to satisfy the seismic design criteria as must complex formwork for the walls which are up to 1.4m thick. The bulky walls, were selected for architectural, rather than structural, reasons – though Smith says that reinforcement needs would demand at least a 600mm thickness. “That is because of California codes, not our calculations.” World famous modernist architect Rafeal Moneo of Spain was selected by the client, the Los Angeles Archdiocese, because of the European tradition he would bring with him. His forms and shapes echo in modern geometric forms, the old high spaces of the great medieval cathedrals and their cruciform layout, though the ‘arms’ of the cross are shortened, and the chapels of the saints face outward rather than inward. It is intended to be a complex and contemplative building inside.

For many of the walls tailor-made lifting formwork will be used to achieve the complex angles and the quality of finish required. “We have had forms made by a cabinet maker’s workshop,” says Dooley. These forms are lifted by the two tower cranes, as is steel and later M&E equipment.

The cranes will also have to do even more delicate work. Despite the seismic restrictions, the architect has chosen to install some of the most sensitive material imaginable for decor: thin sheets of alabaster. These consciously echo stained glass windows in the form of 2.5m-wide, 20m-tall panels of the translucent stone where light will stream in through its delicate veining.

Unfortunately, Spanish alabaster is found only in nodules, allowing sheets no bigger than 1m square to be cut, it breaks relatively easily and worst of all in a city known for its strong sunlight, it is heat sensitive.

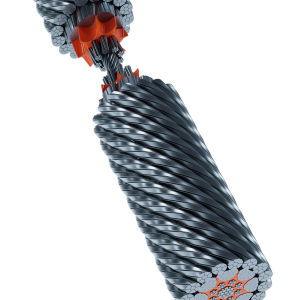

Youseff has devised a special steel truss supporting frame into which shaped sheets of the stone are inserted off site; they will hold together by friction in the frames which will be lifted in by the Liebherrs.