The roles are oddly parallel. Neither are well-paid. Both are seen as a step down from certain colleagues, either doctors or crane drivers. Both can involve long hours in a particular place – the hospital or the work site. Both involve routine jobs that involve interpreting and applying some technical knowledge to a range of different tasks.

Three different speakers at our Crane Safety conference brought up rigging failures as a major contributing factor to crane accidents (see report, p. 15). One of the speakers, Derrick Bailes, publishes a monthly rigging column in our sister magazine Hoist. (An archive is available on www.hoistmagazine.com/leea).

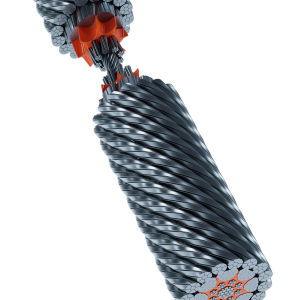

Cranes can only hook things that have lifting points. Every load that does not have pre-engineered lifting points requires the work of a slinger. Some loads are awkward and tricky to bind securely. A rigging job can involve complicated geometry (for sling angles), problem-solving (safely making do in the absence of the perfect equipment) and choosing between materials. Slingers have to think on their feet in a hazardous construction site environment.

I wonder how many crane companies value the training and development of their riggers as much as that of their crane operators, who, after all, control an expensive – and very obvious – asset.